International Man: Broadly speaking, what are the speculative opportunities you see in the commodities markets?

Doug Casey: I’ve traded commodity futures since the mid-1970s. I don’t recommend futures for most investors. It’s not that commodities are more volatile than stocks—they’re not. But, it’s very easy to overleverage with the margin available; I’d say 95% of the public loses money. That said, if you bet the right way on a big move, the results can be breathtaking.

But, let me start by saying that, unknown to the public, commodities have been in a bear market for the last 5,000 years. Most people treat them like growth stocks, and just go long, expecting them to rise.

In fact, the price of commodities—whether we’re talking livestock, grains, tropicals, energy, or metals—has been falling, in real terms, since the dawn of civilization. And that trend will continue.

In primitive times, we had sticks and stones, wild animals, and plants. If you found a little piece of metallic iron from a meteorite, you were the equivalent of a caveman billionaire. The corpse of a dead deer to fend off starvation for another week made you a Big Man. Finding a berry bush was as big a deal as owning a supermarket today.

You needed commodities to live—but they were rare and unprocessed. The whole path of civilization since the end of the last Ice Age, 12,000 years ago, has been about developing technologies to increase the amounts—and lower the costs—of commodities. The Agricultural Revolution that marked the end of the Neolithic Age started the actual Ascent of Man, to use Jacob Bronowski’s phrase. Commodities are the raw materials of civilization.

Starting with the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s, the amounts we could produce skyrocketed, and their costs plummeted. Both of those trends are going to accelerate—radically—because of things like genetic engineering, robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and space exploration. When nanotechnology—the creation of machines at a molecular level—is perfected and comes on stream over the next decade or so, commodity prices will fall to trivial levels. These new technologies are going to make raw materials superabundant and super cheap.

Commodity prices will accelerate their multi-thousand-year-long collapse. They’re basically headed toward zero.

So why would anybody possibly want to be in commodities if they’re in a perpetual bear market? It’s seemingly a paradox.

The answer, however, is that along the way, there are explosive rallies to the upside. Commodities are highly cyclical and can be highly volatile. That, in turn, creates opportunity. Right now, there’s a huge opportunity to the upside. The long-term historical trend is very important to keep in mind—but it’s not very relevant to what will happen over the next five days, five months, or five years.

Why do I expect commodities are entering one of their relatively rare but explosive bull runs? Because most are not only selling at or below the cost of production but also at clear cyclical lows. Commodities are now very cheap in both absolute and relative terms.

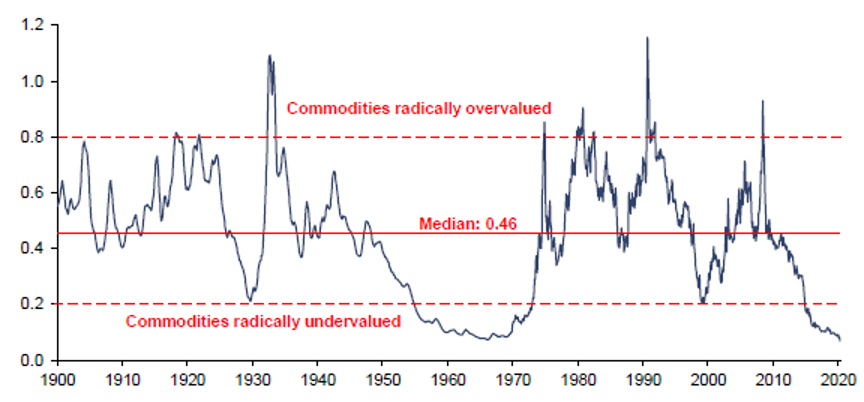

GSCI Commodity Index to the Dow Jones Ratio

Source: Incrementum AG

These are the limiting factors to the downside. Unlike stocks, commodities can’t go to zero. Right now, most commodity producers are just breaking even at best. Most are losing money.

That can’t continue for too long, or producers will go bust and production will collapse. As the building blocks of civilization, you need them to survive. The world uses more of them every year. That’s partly because the world’s population is still growing, partly because it tends to get richer, and partly because new uses are found for most commodities every year.

A hundred years ago, gold was used for money, artwork, and dentistry; now, dozens of new uses are discovered annually in technology, taking advantage of the fact that, among other things, it’s the most ductile, malleable, and inert of all metals.

The 17 rare earth elements were only curiosities 50 years ago; now, they’re critical for hundreds of uses.

There are 92 naturally occurring elements on the periodic table. Everything in the universe is made from them. A century ago, only half of them had uses; now, they all have many uses.

But the development of new uses isn’t the main short-term price driver I’m looking at—that’s been there since Day One. Other factors should interest a speculator now.

Any number of forces majeures loom over the markets. Political upsets and wars typically make commodities soar; there’s a long list of things in those categories.

These are among the macro reasons I think commodities will head higher over the next five years.

Commodities last peaked back in 2011. Many of them are still down 50%. Could they go lower? Anything is possible, of course—we could have a credit collapse deflation, for instance. But that’s unlikely with today’s massively inflationary monetary policy, which puts upward pressure on all prices.

Let me put it this way: As a historian and a technologist, I’m bearish on commodities. But right now, as a speculator, I’m very bullish on commodities.

I like to buy things when they’re demonstrably cheap, and that’s true of commodities right now. They’re about the only area of the financial world that’s not in bubble or even hyper-bubble territory.

International Man: What makes commodity prices and resource stocks so volatile?

Doug Casey: Commodity prices fluctuate for all sorts of reasons. The same is true—on steroids—of mining stocks and resource stocks in general. They have to be viewed as speculations, as opposed to investments. They’re rarely heirlooms; it’s better to view them as trading sardines, not eating sardines.

But that can be a good thing. For example, many of the best speculations have a political element to them. Governments are constantly creating distortions in the market, causing misallocations of capital. Since mining is among the most capital-intensive of businesses, it’s easily affected.

Whenever possible, the speculator tries to find out what these distortions are because their consequences are predictable. They result in trends you can bet on. It’s like the government is guaranteeing your success, because you can almost always count on the government to do the wrong thing.

The classic example, not just coincidentally, concerns gold. The US government suppressed its price for decades—while creating huge numbers of dollars—before it exploded upward in 1971. Speculators who understood some basic economics positioned themselves accordingly.

As applied to metals stocks, governments are constantly distorting the monetary situation. Gold, in particular, being the market’s alternative to government fiat money, is always affected by that. So gold stocks can be a way to short government—or go long on government stupidity, as it were.

The bad news is that governments act chaotically, spastically. The beast jerks to the tugs on its strings held by its various puppeteers. So, it’s hard to predict price movements in the short term. You can bet only on the end results of chronic government fiscal, monetary, and regulatory stupidity.

The good news is that for that very same reason, mining stocks are extremely volatile. That makes it possible, from time to time, to get not just doubles or triples but 10-baggers, 20-baggers, and even 100-to-1 shots.

That kind of upside makes up for the fact that these stocks are lousy investments and that you will lose money on most of them if you hold them long enough. Most are best described as burning matches.

Instead, I like to use fundamentals: supply and demand, production costs, political distortions, technological changes, and the like.

The key takeaway here is that over the long term, all commodity prices fluctuate around the average cost of production.

When a commodity such as hogs trades at significantly more than the cost of production, you can count on producers to flood the market to take advantage of those high prices. When the new product hits the market, it typically collapses the price, perhaps considerably below the cost of production. The market regularly goes from being “too high” to “too low.”

Commodities tend to be cyclical for that reason.

International Man: Recently, the combination of higher production and the effects of the pandemic have caused coffee futures to near a 15-year low.

In fact, Reuters Commodity Desk forecasts that coffee prices could reach as low as $0.6380 a pound in the first half of 2021.

What’s your take on coffee’s supply/demand dynamics?

Doug Casey: Well, they came up that $0.63 number by reading lines on charts. As far as I’m concerned, reading charts is akin to reading tea leaves.

I do find, however, that charts are very valuable for two reasons: One, to give perspective, to show how high or low something is relative to the past. And two, to illustrate what the current trend is. An old rule in commodities is “the trend is your friend; don’t fight the trend.”

Those are the two reasons why charts are important—to me, at least. They are useful for those things, but not predicting.

That said, let’s talk about the fundamentals of coffee for a moment. We could look at hogs again, or cattle. Everything is quite cheap, as the attached chart shows. But coffee is especially interesting, in my view, at about $1.00 a pound. In real terms, that’s close to an all-time low. We could go on for an hour about coffee—but I just want to hit a few points speculators should keep in mind.

Coffee is almost exclusively an export market—after oil, probably the largest in the world. It’s grown by countries around the equator—almost exclusively backward, Third World places. The biggest producer is Brazil, which produces about one-third of the world’s coffee every year.

How do you decide whether coffee is cheap or dear? All commodities fluctuate around their cost of production. Right now, as best as we can determine—taking into account the country, its currency, labor situations, property values, infrastructure, and numerous other things—it’s safe to say that coffee around the world costs somewhere between $1.00 and $1.40 a pound to produce.

Coffee producers are losing money; most are small-holding peasants. It seems there are around 12 million small-holding operations around the world, generally with one, two, or three acres of coffee plants, typically around 600 or so per acre. It’s a very labor-intensive crop; the berries have to be picked by hand. It’s basically subsistence farming for most years.

It’s also a very political crop. We have Pope Francis—who’s philosophically a Peronist, maybe a communist—ranting about the fact that most peasants that actually plant and pick the coffee are working at subsistence levels. That’s a pity, of course. But what can any farmer do if prices are too low to survive? I don’t know what we can do about it, except drink a lot more coffee. Meanwhile, coffee-growing peasants with sense are trying to move to the city where they have a prospect of bettering themselves, as opposed to grubbing for roots and berries.

When we look at coffee over the next decade, it’s going to be hard to keep peasants down on the farm to produce it—there’s likely to be a supply squeeze. Meanwhile, consumption should rise considerably.

The biggest coffee consumers in the world are the Scandinavians who generally use about 20–25 pounds of coffee per year per capita—over triple what Americans use. But coffee drinking is growing worldwide. Europe is by far the largest consumer of coffee, followed by North America and South America. The biggest market, however, is the Orient, where consumption is low, but growing rapidly.

As we go into a nasty depression—which I believe has already started—coffee consumption may drop in relative terms. It’s not an essential food in the way that wheat and corn are.

It takes about five years for a newly planted tree to produce. With that kind of lag, and with today’s poor economics, there aren’t a lot of trees being planted. And, although they can live 50 years, coffee bushes do get old and die. So, raising production is an uphill battle. It’s impossible to increase quickly, not like corn or wheat, where a new crop is planted every year.

When coffee prices are low—like now—the producers try to cut back wherever they can. Fertilizers and pesticides are generally about 5% of the cost of growing the beans. They’re the first things to go because their absence won’t be felt for another year or so. But then next year, you’re going to get fewer beans as a result. It’s very hard for a subsistence farmer to improve his lot in life.

So, what’s the bottom line?

We know coffee is very cheap. We know it’s hard and slow to increase production. We know that—notwithstanding the bad economy—consumption is likely to rise. And there’s an X factor. Coffee is subject to its own pandemics. A variety of fungi, viruses, bacteria, worms, beetles, and parasites can attack the plant. They can wipe out whole crops, unpredictably. And they’re most likely to attack exactly when prices are low and subsistence farmers can least afford to buy the technology to fight them.

Add all of these things together, and I’m a bull on coffee right now. But, it fluctuates radically. A futures contract is 37,500 pounds; that’s the smallest amount of coffee you can buy. If it falls even a penny in a day, your contract is going to go down $375. That’s probably more of a risk than most people want to take, especially if they’re not well-connected coffee specialists.

There are coffee ETFs, of course, but I’m not crazy about ETFs. They don’t actually own the physical coffee. They usually hedge in the futures market, where the managers can make serious mistakes. The bottom line is the coffee market is mainly for big boys. The best way to play it may be buying far out commodity options.

All the caveats aside, however, I think coffee is an excellent speculation. If it goes from current levels of $1.00 back to the previous highs of over $3—which it last hit in 1997 and 2011—each contract of coffee, which has a minimum margin of $5,400, could make you $75,000 from here. $5 coffee isn’t out of the question.

International Man: Looking at the fundamentals, are we close to the bottom of the cycle for commodities?

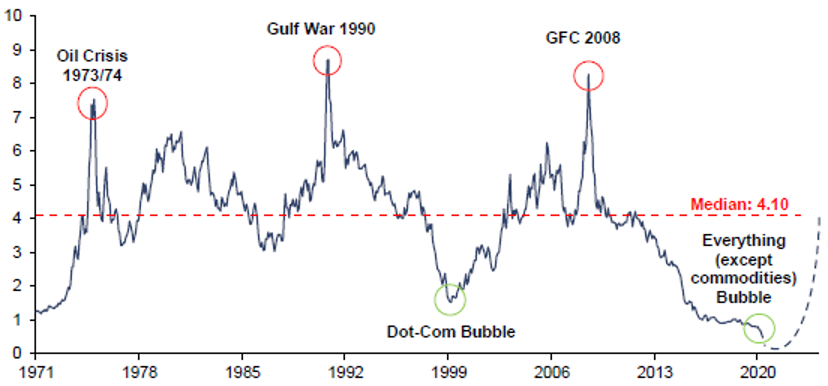

Doug Casey: Depending on which index we look at, commodities have come down 50–80% or more since the peak in 2011.

GSCI Commodity Index to the S&P 500 Ratio

Source: Incrementum AG

Gold is the only commodity that’s really been strong. Most have done very badly. That’s especially interesting in that the stock market is close to all-time highs. So, why have commodities been so weak in the face of all the money creation that’s driven stocks?

One reason, of course, is that the economy hasn’t been very strong. Most economic activity hasn’t been about producing hard goods—it’s been about bytes and bits, computers and software. Commodities have been relatively unused.

It’s also a concern that during the depression of the 1930s, commodities sold below the cost of production for years. Could that happen again? It’s possible.

Take agricultural commodities. The amount of corn, wheat, or soybeans that can be grown per acre increases consistently with improvements in technology. That’s not just true of grains, however—it’s true of everything.

That includes gold. In Roman times, a gold deposit had to be at least an ounce per tonne to be economic. Now, deposits can be economic at a hundredth-of-an-ounce per tonne.

It’s similar with most metals. Copper ore, for instance, used to need at least a couple of per cent grade to be economic. Today, a large deposit can be profitable at .2%, although some deposits in the Congo go up to 20% per tonne. These are incredible numbers, but the political situation makes mining very risky there.

Technology works to reduce the production costs of all commodities, not just metals and grains. That trend will continue as biotechnology improves and nanotechnology comes online. In addition, tech improvements mean commodities are used more efficiently. For example, cars used to get 12 miles per gallon, and now, they get 35—and they go much faster.

International Man: We’ve seen precious metals like gold and silver take off. Where do you think commodities as a group are headed?

Doug Casey: Commodities are volatile and cyclical. That won’t change.

But the gigantic amounts of money and credit being created will have a huge effect on commodity prices.

I don’t know when the explosive turnaround will occur—it could be tomorrow morning or a year from now. I thought it would have been a couple of years ago.

It’s wise to keep an eye on commodities, but few people do. Nobody is talking about them. Nobody’s interested in them.

The public is totally uninvolved and unknowledgeable about commodities. The average American doesn’t even know milk comes out of a cow—they think it comes out of a carton. The situation is analogous for all commodities.

That’s a setup for a huge bull market.

Editor’s Note: Legendary investor and NY Times best selling author, Doug Casey just released an urgent video which outlines exactly how he’s positioning to profit from this rare opportunity.

He discusses how this situation has played out numerous times in his career and why even a small amount of money put into the right stocks today could deliver life-changing rewards. Click here to watch it now.

Source: https://internationalman.com/articles/doug-casey-on-what-makes-commodity-prices-so-volatile/