The terms liberal (left) and conservative (right) define the conventional political spectrum. But the terms are floating abstractions, with meanings that change with every politician.

In the nineteenth century, a “liberal” believed in free speech, social mobility, limited government and strict property rights. The term has since been appropriated by those who, while sometimes still believing in limited free speech, always support strong government and weak property rights and who see everyone as a member of a class or group.

Conservatives have always tended to believe in strong government and nationalism. Bismarck and Metternich were archetypes. Today’s conservatives are sometimes seen as defenders of economic liberty and free markets, although that is mostly only true when those concepts are perceived to coincide with the interests of big business and economic nationalism.

Locating political beliefs on an inaccurate scale, running only from left to right, constrains political thinking. It’s like trying to reduce chemistry to the elements with air, earth, water and fire.

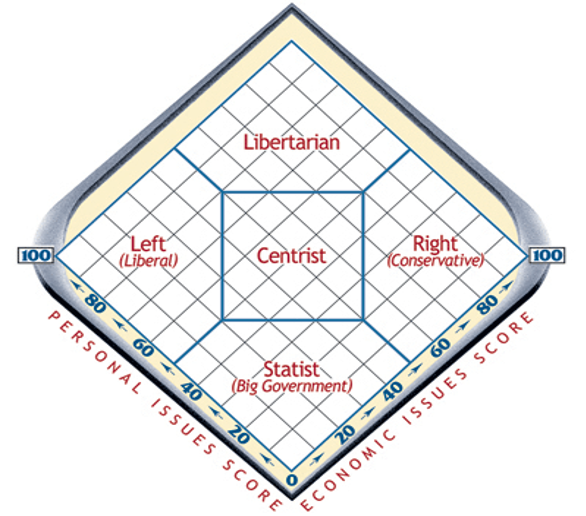

Politics is the theory and practice of government. It concerns itself with how force should be applied to control people, which is to say, to restrict their freedom. It should be analyzed on that basis. Freedom is indivisible, but in the abstract, it can be seen as composed of two basic elements: social freedom and economic freedom. According to current usage, liberals tend to allow social freedom but restrict economic freedom, while conservatives tend to restrict social freedom but allow economic freedom. An authoritarian (they now style themselves “middle-of-the-roaders”) want both types of freedom restricted.

But what do you call someone who believes both social and economic freedom should be allowed maximum rein? Unfortunately, something without a name may get overlooked, or if the name is only known to a few, it may be ignored as unimportant. That may explain why so few people who believe in both of these dimensions of freedom know they are libertarians. A more useful way of looking at the political field can be found in the diagram below:

A libertarian believes individuals have a right to do anything that doesn’t impinge on the common-law rights of others—basically anything but force or fraud. Libertarians are the human equivalent of the Gamma rat, which bears a little explanation. Some years ago, scientists experimenting with rats categorized the vast majority of their subjects as Beta rats. These are followers who get the Alpha rats’ leftovers. The Alpha rats establish territories, claim the choicest mates, and, generally, lord it over the Betas. This pretty well corresponded with the way the researchers thought the world worked.

But they were surprised to find a third type of rat as well, the Gamma. This creature staked out a territory and chose the pick of the litter for a mate, like the Alpha, but didn’t attempt to dominate the Betas, a go-along-get-along rat. A libertarian rat, if you will. My guess, mixed with a dollop of hope, is that as society becomes more repressive, more Gamma people will tune in to the problem and drop out as a solution. No, they won’t turn into middle-aged hippies weaving baskets and stringing beads in remote communes; rather, they will structure their lives so that the government—which is to say taxes, regulation, and inflation—is a nonfactor. Hippies used to ask: suppose they had a war and nobody came? Personally, I would take it further: suppose they had an election and nobody voted; levied a tax and nobody paid; imposed regulation and nobody obeyed?

Libertarian beliefs are strong among Americans, but the Libertarian Party has never gained much prominence, possibly because the type of people who might support it have better things to do than play political games. Even among those who believe in voting, many tend to feel they are “wasting” their vote on someone who can’t win. But voting is itself another part of the problem.

None of the Above

Since 1960, the trend has been for an ever-smaller percentage of the electorate to vote. Increasingly, the average person is fed up or views elections as pointless. In some years, more than 98 percent of incumbents retain office. That is a higher proportion than in the Supreme Soviet of the defunct U.S.S.R., and a lower turnover rate than in Britain’s formerly hereditary House of Lords, where people lost their seats only by dying. The political system in the United States has, like all systems that grow old and large, become moribund and corrupt. The conventional wisdom holds that this decline in voter turnout is a sign of apathy. But it may also be a sign of a renaissance in personal responsibility. It could be people saying: “I won’t be fooled again, and I won’t lend power to them.” Politics has always been a way of redistributing wealth from those who produce to those who are politically favored. As H. L. Mencken observed, an election amounts to no more than an advance auction of stolen goods—a process few would support if they saw its true nature. Protesters in the ’60s had their flaws, but they were quite correct when they said, “If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem.” If politics is the problem, what is the solution? I have several answers that may appeal to you.

The first step in solving the problem is to stop actively encouraging it. Many Americans have intuitively recognized that government is the problem and have stopped voting. There are at least five reasons many people don’t vote:

- Voting in a political election is unethical. The political process is one of institutionalized coercion and force; if you disapprove of those things, then you shouldn’t participate in them, even indirectly.

- Voting compromises your privacy. It gets your name in another government computer.

- Voting, as well as registering, entails hanging around government offices and dealing with petty bureaucrats. Most people can find something more enjoyable or productive to do.

- Voting encourages politicians. A vote against one candidate—a chief, and quite understandable, reason many people vote—is always interpreted as a vote for his opponent. And even though you may be voting for the lesser of two evils, the lesser of two evils is still evil. It amounts to giving the candidate a tacit mandate to impose his will on society.

- Your vote doesn’t count. Politicians like to say it counts because it is to their advantage to get everyone into a busybody mode. But statistically, one vote in scores of millions makes no more difference than a single grain of sand on a beach. That’s entirely apart from the fact that officials manifestly do what they want, not what you want, once they are in office.

Some of these thoughts may impress you as vaguely “unpatriotic”; it’s certainly not my intention to “trigger” anyone. But unfortunately, America isn’t the place it once was, either. The United States has devolved from the land of the free and the home of the brave to something more closely resembling the land of entitlements and the home of whining lawsuit filers. The founding ideas of the country, which were intensely libertarian, have been thoroughly perverted. What passes for tradition today is something against which the Founding Fathers would have led a second revolution.

This sorry, scary state of affairs is one reason some people emphasize the importance of joining the process, “working within the system” and “making your voice heard,” to ensure that “the bad guys” don’t get in. They seem to think that increasing the number of voters will improve the quality of their choices. That argument compels many sincere people, who otherwise wouldn’t dream of coercing their neighbors, to take part in the political process. But it only feeds power to people in politics and government, validating their existence and making them more powerful in the process.

Of course, everybody involved gets something out of it, psychologically if not monetarily. Politics gives many people a sense of belonging to something bigger than themselves, and so has special appeal for those who can’t find satisfaction within themselves. We cluck in amazement at the enthusiasm shown at Hitler’s giant rallies but figure that what goes on here, today, is different. Well, it’s never quite the same. But the mindless sloganeering, the cult of personality and certainty of the masses that “their” candidate will kiss their personal lives and make them better are identical.

And even if the favored candidate doesn’t help them, then at least he’ll keep others from getting too much. Politics is the institutionalization of envy, a vice that proclaims: “You’ve got something I want, and if I can’t get it, I’ll take yours. And if I can’t have yours, I’ll destroy it, so you can’t have it, either.” Participating in politics is an act of ethical bankruptcy.

The key to getting “rubes” (i.e., voters) to vote, and “marks” (i.e., contributors) to give is to talk in generalities while sounding specific and to look sincere and thoughtful yet decisive. Vapid, venal party hacks can be shaped, like Silly Putty, into saleable candidates. People like to kid themselves that they are voting for either “the man” or “the ideas.” But few campaign “ideas” are more than slogans artfully packaged to push the right buttons. Voting “the man” doesn’t help much, either, since these guys are more diligently programmed, posed and rehearsed than any actor.

This is probably truer today than it has ever been since elections are now won on television, and television is not a forum for expressing complex ideas and philosophies. It lends itself to slogans and glib people who look and talk like game show hosts. People with really new ideas wouldn’t dream of introducing them to politics because they know such ideas can’t be explained in sixty seconds. I’m not intimating, incidentally, that people disinvolve themselves from their communities, social groups, or other voluntary organizations—just the opposite since those relationships are the lifeblood of society. But the political process or the government is not synonymous with society or even complementary to it. The government is a dead hand on society.

“Wait, wait,” I can hear many of you saying, “That may all be true in theory. But it’s irrelevant in 2020; this time it’s different. We’re on the cusp of a civil war in the US. It makes a big difference who wins this time.” That’s true enough. Whoever runs a government can, indeed, make a huge difference sometimes. France was different under Louis XVI than it was under Robespierre, and Russia was different under Nicolas II than it was under Lenin. At this point, the US will be different under Trump than under the Democrats.

I’ll explore the likelihood of a Trump victory or loss next week.

And what happens next.

Editor’s Note: Disturbing economic, political, and social trends are already in motion and now accelerating at breathtaking speed. Most troubling of all, they cannot be stopped.

There will likely be unprecedented volatility of every kind in the months and years ahead.

That’s exactly why bestselling author Doug Casey and his team just released a free report with all the details on how to survive the crisis ahead.

It will help you understand what is unfolding right before our eyes and what you should do so you don’t get caught in the crosshairs.

Source: https://internationalman.com/articles/how-to-solve-the-problem-of-politics-in-the-divided-states-of-america/